Collection: CRAFTED - Voices of the Creators vol.1

Megumi Shimamoto, Hyobodo

Located in Uzumasa, Ukyo Ward, Kyoto City, Hyobodo is a lacquerware workshop established in 2014 by Megumi Shimamoto, her husband Terunori Sugimoto, and restoration specialist Yoko Nakamichi. The workshop works on traditional Kyoto lacquerware such as tea ceremony utensils and lacquered bowls, as well as the restoration of shrines, temples, and cultural properties. While carrying on the tradition of lacquerware crafts, they are also enthusiastic about trying to express the charm of lacquerware in modern life, such as in interior design and art pieces.

Representative director Megumi Shimamoto is an artisan who breathes fresh air into lacquerware, a field that is often associated with lacquered bowls and maki-e tiered boxes, with her original works.

Changing the image of lacquerware as a special occasion or Japanese tableware

Megumi Shimamoto won the Grand Prix at the Kyoto Crafts and Design Competition "TRADITION for TOMORROW" 2024–2025 (*).

Her award-winning piece is a small vessel made from a sea urchin shell decorated with lacquer and maki-e. Inspired by the French bonbonnière, a vessel used for sweets, she named it Bonbounnière.

The shell comes from the sea urchin "Gangase", which has proliferated in large numbers and damaged marine ecosystems. The work also conveys a message about the environment and the cycle of life.

(*) Kyoto Crafts and Design Competition "TRADITION for TOMORROW" 2024-2025: A craft competition to be held from 2024 by the Kyoto Museum of Crafts and Design (Kyoto Industrial Promotion Center Corp.) with the aim of connecting Japan's traditional culture and traditional industries to the future.

“Japanese culture has an aesthetic of mitate—seeing one thing as something else. I hope people will appreciate how natural forms can be reborn as tools,” says Shimamoto.

One unique work using natural materials is the Bamboo-Spliced Glass, in which the stem of a wine glass is repaired with bamboo. The strong adhesive power of lacquer unites the very different materials of bamboo and glass, evoking warmth both in its appearance and in the spirit of mending with care

Her Maki-e and Raden Glass applies techniques usually reserved for black lacquer to transparent glass. Using an extremely fine brush, she paints patterns in lacquer, sprinkles gold powder to set them, and inlays delicate shell fragments along the curved surface. The shimmering interplay of gold and iridescent shell under the light represents a completely new expression of lacquerware, long admired as a symbol of the aesthetics of shadow in Jun’ichirō Tanizaki’s In Praise of Shadows (*).

These surprising and inventive expressions of lacquer have earned Shimamoto numerous awards.

(※)Maki-e and Raden: Decorative techniques in which patterns are painted with lacquer and sprinkled with metallic powder (maki-e), or inlaid with thin pieces of mother-of-pearl (raden).

(※)In Praise of Shadows: An essay by Jun’ichirō Tanizaki (1933) that argues Japanese beauty is shaped by shadow, praising lacquerware as an embodiment of this aesthetic.

Shimamoto's creative inspiration comes from finding beauty in nature and observing it deeply.

"I love fieldwork, and I go out into beautiful landscapes and pick up things to use as materials. When I see something beautiful, I think, 'I want to make use of it,' 'I want to preserve it.'"

Shimamoto sees the potential in the natural form, shines light on it, and transforms it into a work of art using lacquer.

I first encountered lacquer in a Japanese painting class.

The joy of "my art becoming someone else's tool"

Her first encounter with lacquer was when she tried maki-e in a Japanese painting class. "Just like Japanese painting, you draw a picture, but with maki-e, the picture and the object become one. I felt joy in knowing that my picture could become a tool that someone could use."

After graduating from university, Shimamoto further studied lacquer under lacquer artist Koken Murata. What drew her to lacquer was its profound history.

"The oldest lacquer in the world was excavated from ruins from the Jomon period in Japan. It remains like a time capsule, along with the techniques used. Is there any other material like this?"

The work of restoration gives us the strongest sense of that history.

"When I see old lacquerware, I feel that the things that people of the past did for me are connected to me, that I am with them, and it gives me a sense of purpose."

When working on restoration projects, she says she switches her mindset from when she creates personal works.

"The work involves listening to experts and consulting with multiple people, so you have to take into account the thoughts and prayers of many different people. It's a completely different way of thinking than creating your own work."

In recent years, lacquer has been attracting increasing attention from the interior and architectural fields, and Hyobodo has been receiving an increasing number of requests to create works with unprecedented uses and on a scale.

"I've been consulted on a variety of projects, including interior design for luxury hotels, restaurants, and entrance décor for apartment buildings. Every time, I think, 'There's no way I can do this, right?' (laughs), but I give it a try anyway."

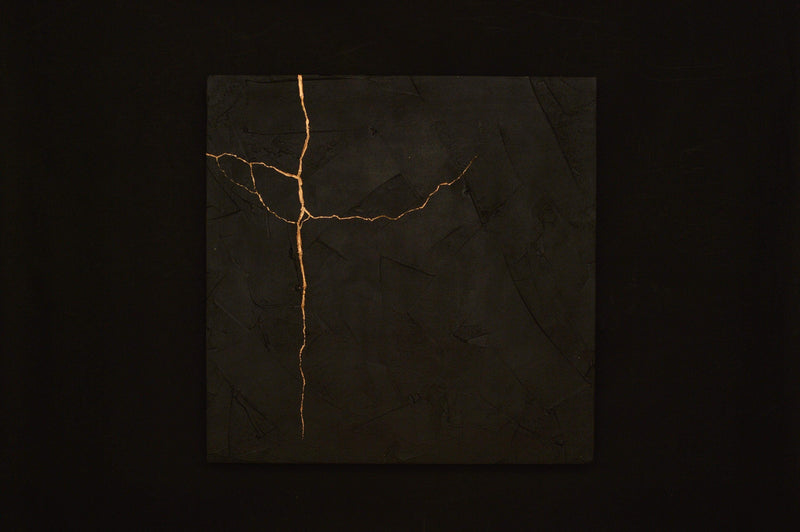

At the design show "Maison & Objet"* (2018-2019) in Paris, I deliberately exhibited a large lacquer board rather than lacquerware. I applied various lacquer techniques, such as brush marks, "negoro-nuri* ", "byakudan-nuri* ", and "sabiurushi* ", to the flat surface, and the work simply showcased the texture and technique of lacquer itself.

"Most people in Japan, as well as overseas, are unfamiliar with lacquerware. I wanted this piece to be a gateway for people to learn about lacquerware."

(*) Maison&Objet: The world's largest international interior design and lifestyle fair held in Paris, France

(*) negoro-nuri : A technique in which red lacquer is applied over black lacquer. With use, the black beneath wears through, creating a unique interplay of red and black.

(*) byakudan-nuri : A technique where transparent lacquer is layered over gold leaf or designs, allowing them to faintly show through and produce an elegant, amber-like glow.

(*) sabiurushi : A mixture of lacquer and finely ground wood powder (tonoko), mainly used as an undercoat to strengthen and smooth the surface.

While often used as a foundation, it can also create the appearance of rusted metal.

Photo courtesy of Hyobodo

Inheriting Kyoto’s spirit of craft innovation

Shimamoto’s stance of facing her era and exploring the present and future of lacquer may be linked to her training under innovative Kyoto lacquer artists.

In the 1970s, Kyoto artisans experimented with lacquer expressions incorporating new materials such as acrylic and cashew. Shimamoto studied under Koken Murata, a disciple of lacquer artist Shunshō Hattori, who was a member of the ambitious group Forme (1970–78).

“My teacher said, ‘Just because it’s a traditional craft doesn’t mean it has to be one way.’ At the same time, he taught, ‘When history, your own skills, and Japanese values all reach their height together, great works are created.’ I realized you must pursue both tradition and creativity.”

Photo courtesy of Hyobodo

Passing on skills while advancing one's own expression

Hyobodo is celebrating its 10th anniversary. Shimamoto says, "We are the generation that discovers new things about lacquer," and looks ahead to her goals. She wants to create and communicate new appeal to lacquerware, which has become largely reserved for special occasions. She also feels a heavy responsibility to connect Kyoto's lacquerware industry to the future.

In the past, Kyoto craftsmen produced masterpieces through division of labor. Lacquerware production involves many steps, from preparing the wood base to painting and decorating. There was a system in place where specialized craftsmen worked together to complete these steps.

"What existed in the past may not always exist in the future. When setting up the workshop, my husband said, 'I want to be a fundamental support for Kyoto lacquerware.' The number of artisans who have traditionally carried out a division of labor is dwindling, and it may also become more difficult to obtain materials and tools. I want our workshop to be one that can respond to whatever happens in the future and continue to support lacquerware."

Shimamoto is a modern-day craftsman who takes on many tasks, including creating her own lacquerware, working in her workshop, and creating an environment for the future of the lacquer industry. She is also building her career by meeting and challenging new needs for lacquer that have never existed before, and enjoying tradition as something dynamic.

"I am carrying on what has been passed down from the past, and taking my own expression and my own life one step further. I create every day with this in mind."

-

Bamboo splicing glass (various types) / no.3385

Regular price €110,95Regular priceUnit price / per -

Maki-e and Raden Glass "Violet" / no.3153

Regular price €430,95Regular priceUnit price / per -

Maki-e and Raden Glass, Three-Colored Violet / no.3154

Regular price €430,95Regular priceUnit price / per -

Bonbauniere (various types)/ no.3146

Regular price €110,95Regular priceUnit price / per -

Sakeware shuran / no.3155

Regular price €221,95Regular priceUnit price / per -

Incense container Chikubushima / no.3156

Regular price €922,95Regular priceUnit price / per -

Set of 2 Maki-e cutlery rests / no.3157

Regular price €92,95Regular priceUnit price / per -

Set of 2 mother-of-pearl spoons / no.3158

Regular price €61,95Regular priceUnit price / per -

Lacquer Yunomi / 2 types

Regular price €24,95Regular priceUnit price / per